Harvesting your intentions: Tumblr’s David Karp meets Zygmunt Bauman

Shortly after Yahoo confirmed its plans to purchase Tumblr for $1.1 billion, Charlie Rose interviewed 26-year-old Tumblr founder and CEO David Karp. Karp was wearing his signature gray hoodie. Rose sported a purple tie. I was struck by what Karp had to say about advertising.

Shortly after Yahoo confirmed its plans to purchase Tumblr for $1.1 billion, Charlie Rose interviewed 26-year-old Tumblr founder and CEO David Karp. Karp was wearing his signature gray hoodie. Rose sported a purple tie. I was struck by what Karp had to say about advertising.

Here’s the set-up:

Rose: What excites you the most? The building of the business or creating the product?

Karp: So, we have this … ah … look. The product is why I got into this. I have to tell you that the business end of this has become such an interesting, exciting, fun challenge for us, because we’ve got this thesis that we can build a business that not only does not compromise everything that is special about Tumblr – makes it such an incredible home for these incredibly talented people – but actually makes Tumblr a better place. In the same way that, you know, if you ripped all the ads out of Vogue, one, it would be half the magazine, but two, it would actually lose a lot of the great content. The way we’ve approached advertising doesn’t look anything like advertising across the rest of the Internet today. So much of …. There’s a lot of nuance here, but, you know, so much of …

Rose: But explain it to me,

Karp: Sure, sure, sure.

Rose: … because it’s the essence of what you’re trying to do.

But here’s where it gets really interesting (my emphasis added) – where Karp expands on what will make Tumblr a “better place.”

Karp: We’ve gotten so used to advertising being something that pulls you over when you’re in this mode to, like, buy an iPod and go buy it from Best Buy rather than over here. It’s something people in Silicon Valley call “harvesting intent.” So take somebody who’s looking for something and go send them to do it over here, and get them to convert as quickly as possible.

What advertising and media used to be was story telling. Something that used to get you to aspire to a lifestyle. Something that got me, you know, as a kid, growing up in Manhattan, somebody who should never have any reason to want a car, yet those BMW ads and those cars screaming around those, like, you know, curvy roads on that mountain, made me really aspire to want a car. And you know when I turned 18, and you have to be 18 in New York City to get your driver’s license, or to drive.

Rose: 16 in North Carolina.

Karp: I know. I know. Believe me. It killed me. It killed me growing up. It made me go out and get a car when I turned 18. So ads … have …

Rose: Ads create desire?

Karp: They create intent. And so much of what the web has spent time, or I should say, what the big networks on the Internet, in the last decade, have spent time focusing on, is something that Google really pioneered and proved to be a huge, huge business, but it’s really focused on – once you’ve already got their interest, getting you to convert. Getting you to make the purchase. But there’s a whole other world of creative advertising, brand advertising. Ads that get you to aspire to a lifestyle, get you to aspire to something. Because why people got into the ad industry. They got in with Mad Men aspirations, right? They want to like write the hook. Write the jingle that actually makes a gal, like, “Oh yeah, I should … I want, like … I want to go finance, like, a little coupe that I blaze around in on the weekends.” You know … that’s like … that’s what great advertising has always done, and the great thing about great advertising is to be great.

What I find remarkable here is what I hear Karp saying: “Please — manipulate me. I don’t know what I want or what I should do unless you show me. Sweep me up into the life I see in tony magazines and high-end ads. Convert me! Harvest me! Lead me to inspire my 100 million Tumblr users to aspirations of their own conversion and harvesting, as I was inspired. And like… wow… isn’t great advertising great!”

I am fond of nerds and geeks. I am one. And I respect and am maybe a little in awe of the talented Mr. Karp. But I have to wonder just how common it is to so enthusiastically embrace one’s own manipulation and psychological harvesting. I’m almost afraid to find out.

Consumable relationships

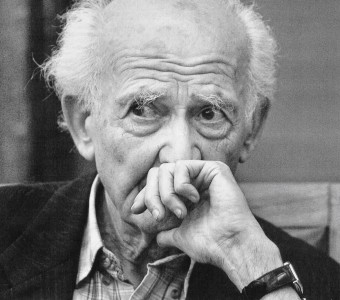

While I was thinking about this, I happened to be reading Zygmunt Bauman’s book Identity. Bauman differs from Karp in his assessment of the seductive appeal of advertising. He relates the pursuit of “consumables” to a “predicament” we experience in our personal relationships: We have come to prefer our wide but shallow digital communities over the complexity and awkwardness of real, live, face-to-face contact. (See also Alone Together on this point.)

While I was thinking about this, I happened to be reading Zygmunt Bauman’s book Identity. Bauman differs from Karp in his assessment of the seductive appeal of advertising. He relates the pursuit of “consumables” to a “predicament” we experience in our personal relationships: We have come to prefer our wide but shallow digital communities over the complexity and awkwardness of real, live, face-to-face contact. (See also Alone Together on this point.)

Exposed to the ‘contacts made easy’ by electronic technology, we lose the ability to enter into spontaneous interaction with real people. In fact, we grow shy of face-to-face contacts. We tend to reach for our mobiles and furiously press buttons and knead messages in order to avoid making ourselves hostage to fate — in order to escape from complex, messy, unpredictable, difficult to interrupt and to opt out from interactions with those ‘real people’ physically present around us. The wider (even if shallower) our phantom communities, the more daunting appears the task of sewing together and holding together real ones.

For Bauman, the appeal of advertising is not the creation of aspirations, but relief from our predicament: a consumer lifestyle redirects emotions from human relationships to consumable things.

As always, consumer markets are all too eager to help us out of the predicament. Taking a hint from Stjepan Mestrovic [Postemotional Society], Hargreaves [Teaching in the Knowledge Society] suggests that ’emotions are extracted from this time-starved world of shrinking relationships and reinvested in consumable things. Advertising associates automobiles with passion and desire, and mobile telephones with inspiration and lust.’ But however hard the merchants try, the hunger they promise to satiate won’t go away. Human beings may have been recycled into consumables, but consumables cannot be made into humans. Not into the kinds of humans that inspire our desperate search for roots, kinship, friendship and love — not humans one could identify with.

Earlier, speaking of the nature of contemporary relationships, Bauman uses the image of the rufuse bin: “Partnerships instantly entered, fast consumed and disposed of on demand have their unpleasant side-effects. The spectre of the rubbish heap is never far away.” What’s so appealing about the consumer lifestyle, Bauman argues, is that it shields us from the threat of the refuse bin in our in-person relationships.

It needs to be admitted that consumable substitutes have an edge over the ‘real stuff’. They promise freedom from the chores of endless negotiation and uneasy compromise; they swear to put paid to the vexing need for self-sacrifice, concessions, meeting half-way that all intimate and loving bonds will sooner or later require. They come with an offer of recuperating your losses if you find all such strains too heavy to bear. Their sellers also vouch for an easy and frequent replacement of goods the moment you no longer find a use for them, or when other, new, improved and still more seductive goods appear in sight. In short, consumables embody the ultimate non-finality and revocability of choices and the ultimate disposability of the objects chosen. Even more importantly, they seem to put us in control. It is we, the consumers, who draw the line between the useful and the waste. Having consumables for partners, we can stop worrying about ending in the refuse bin. Or can we?

During the lifetime of Zygmunt Bauman (he’s now 87), the nature of society and the individual, including our sense of community, friendship and intimate relationships, has been permanently altered. Nostalgia will not bring them back. David Karp is enthusiastic about the present into which he was born. He will grow old in what may seem, to those who preceded him, like a science fiction novel they read in their youth. That future is all too real, however. Or is it?

Related posts:

Bruckner on the good life, money, and the unequal world of work

Why do we feel bad about the way we look?

The unavoidable and burdensome responsibility to be happy

The death of Wang Bei: Cosmetic surgery as a moral choice

This mess we’re in – Part 3

A generation obsessed with material wealth

Image source: David Karp: Business Insider. Zygmunt Bauman: Octaedro

References:

Charlie Rose interview with Tumblr CEO David Karp, May 29, 2013

Zygmunt Bauman, Identity: Coversations with Benedetto Vecchi

Andy Hargreaves, Teaching in the Knowledge Society: Education in the Age of Insecurity

Sherry Turkle, Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other

Stjepan G. Mestrovic, Postemotional Society

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.