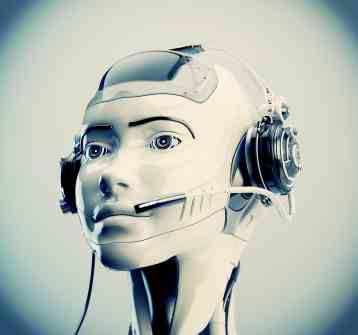

Just how extensively will jobs be lost to automation?

New Scientist recently interviewed Andrew McAfee, one of the authors of The Second Machine Age: Work, progress and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies. McAfee and co-author Erik Brynjolfsson are experts in digital technologies and economics (their previous book was called Race Against the Machine: How the Digital Revolution Is Accelerating Innovation, Driving Productivity, and Irreversibly Transforming Employment and the Economy). A basic question raised in the interview (and addressed in the book) is whether advances in technology will greatly reduce the need for human labor, leaving a large segment of the population unemployed. Their answer, basically, is ‘yes.’

New Scientist recently interviewed Andrew McAfee, one of the authors of The Second Machine Age: Work, progress and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies. McAfee and co-author Erik Brynjolfsson are experts in digital technologies and economics (their previous book was called Race Against the Machine: How the Digital Revolution Is Accelerating Innovation, Driving Productivity, and Irreversibly Transforming Employment and the Economy). A basic question raised in the interview (and addressed in the book) is whether advances in technology will greatly reduce the need for human labor, leaving a large segment of the population unemployed. Their answer, basically, is ‘yes.’

In the interview, McAfee describes three possible scenarios. One, the disruptions could be more or less temporary. Technology has been eliminating the need for human labor in various segments of the workforce for hundreds of years now. But technology also creates new jobs. If it can do that fast enough, workers can be retrained, avoiding extensive periods of high unemployment.

Two, there could be successive waves of automation that have a much larger impact than anything we’ve experienced in the past. Automated driving, for example, will eliminate jobs that require a human driver. While this is but one of many examples of automation, it is by no means insignificant. According to the latest US census estimates, the largest occupation category among men was truck driver, employing 3.2 million people. The point is, in this scenario it will be difficult for the economy to adjust simply by retraining workers.

Three, the need for labor could be dramatically reduced. This is the scenario McAfee believes is most likely. There will still be a need for those entrepreneurs who create and perfect even more automation, but the rest of us will not be needed. Read more